Court of Rome brings Italian case law on distinctiveness into line with that of ECJ

The Specialised IP Division of the Court of Rome has issued an important decision on the issue of distinctiveness.

On July 21 2014 the court upheld a previous decision issued on March 4 2014 in urgency proceedings brought by a Perugia-based fashion company (Emerald srl) and its chief executive officer against the Italian Rugby Federation and an advertisement agency (Red Hot Fashion srl). The court held that the trademark for which Emerald sought protection – against an advertising campaign spread mainly through Twitter that was aimed at rallying Italian rugby fans – lacked distinctiveness, even though its component elements were neither generic nor descriptive, because the public would not perceive it as evoking a distinctive message.

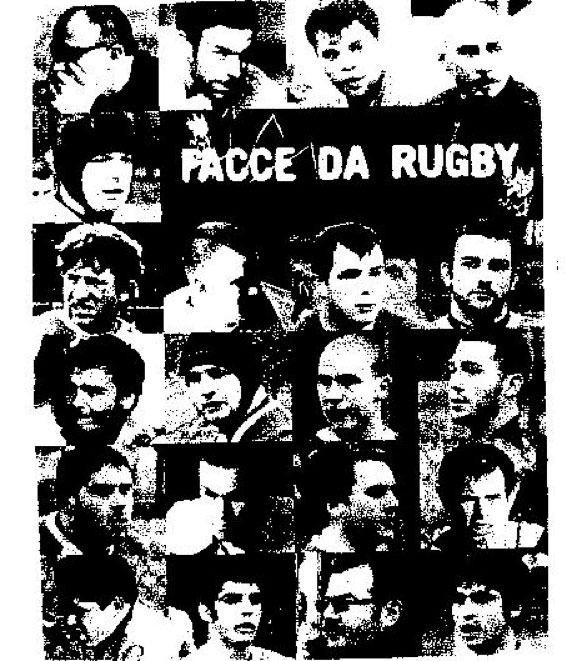

The trademark at issue (depicted below) included the words ‘facce da rugby’ (‘faces of rugby’), together with a series of small squares containing portraits of rugby players.

The court held that these elements, even when combined, would be perceived by the relevant public not as an indication of the source of the products, but only as a generic advertisement, which could be used for any kind of product or activity concerning the sport of rugby. This was confirmed by the activity of the alleged infringers, which consisted of an advertising campaign (created by Red Hot Fashion for the Italian Rugby Federation) based on use of the hashtag ‘#faccedarugby’ (which, in a single case, was combined with square pictures of rugby fans) and was aimed at promoting the sport of rugby in Italy.

What makes the court’s order particularly important are the grounds for the decision, which expressly abandoned the position traditionally held by Italian legal theory and case law, whereby generic names and descriptive indications constituted an exhaustive list of signs lacking distinctive character. Therefore, in practice, the requirement that a mark have distinctive character was interpreted ‘negatively’ – that is, a mark had distinctive character if it did not consist of the generic name of the product/service at issue or a related descriptive indication.

This old-fashioned position had been widely criticised in Italy, since it was clearly reductive from various perspectives. First, it is clear that the rationale which forbids the monopolisation of generic names and descriptive indications also applies to non-denominative signs which express, in a general manner, the characteristics of the product or service bearing the mark, such as images representing the product/service or packaging in the shape of the goods. By preventing the appropriation of generic signs as trademarks, the aim is to prevent a monopoly on a sign from turning into a monopoly on the product itself. According to EU case law, this “pursues an aim which is in the public interest, namely that such signs or indications descriptive of the characteristics of the goods or services in respect of which registration is applied for may be freely used by all”.(1)

Second, trademarks which “consist exclusively of signs which have become customary in the common language or in the bona fide and established practices of the trade” cannot be registered, since they lack distinctiveness. According to traditional case law and legal theory in Italy, such signs consist of denominations or (two or three-dimensional) symbols which, although lacking descriptive character, are “commonly used in trade and in daily life for goods of any type (eg, words such as ‘super’, ‘extra’ and ‘standard’)”.(2)

However, with regard to numbers and letters, ambiguity remained: it was clear that ‘generic’ use of letters and numbers could be permitted, even where the number or letter was registered as a trademark by a third party, if it fell within the scope of lawfulness recognised by Article 21, Paragraph 1 of the Code of Industrial Property and Article 12 of the EU Community Trademark Regulation (207/2009) (descriptive use of another’s sign), provided that such use was “in accordance with honest practices”. On the other hand, improper use of such signs was forbidden (ie, when such use created a likelihood of confusion or a parasitical link to the trademark). A trademark consisting of a single letter or number would therefore be accepted if, in a certain context, that single letter or number was actually perceived as a distinctive sign (ie, as bearing a message relating to the existence of an exclusive right) and was protected against any use which brought to mind that specific message, and not (or not only) against the ‘generic’ message relating to the type of goods.

However, these cases did not provide an exhaustive list of signs which lack distinctive character. As stated by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and expressly quoted by the Court of Rome, there are signs which, although they are neither descriptive nor in general use, are unable to communicate a ‘message’ – in particular, a distinctive message. According to the ECJ, the existence of the requisite capacity to distinguish must also be assessed positively,(3) rather than only negatively. It appears clear from EU case law that this is, in a sense, a ‘residual’ impediment, considered essentially for signs which, in the eyes of the public, do not normally have a distinctive function.

This situation arises in particular for trademarks consisting of colours, the shape of the product or the shape of packaging and – as the ECJ highlighted – also for slogans. The decision at issue seems to be inspired mainly by the EU case law on slogans. According to the ECJ, “average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of products on the basis of such slogans”.(4) However, this statement at least partly conceals an ambiguity: it may apply only to signs which have been created as slogans – that is, signs which, due to their structure, cannot plausibly be perceived in any other way. In contrast, when only their use allows the public to define signs as slogans or as distinctive signs, the process is reversed to some extent (ie, where the use leads to a loss of distinctive character).(5)

The decision in the present case seems to indicate that, with regard to the issue of distinctiveness, Italian case law is now fully aligned with that of the ECJ.

For further information on this topic please contact Cesare Galli at IP Law Galli by telephone (+39 02 5412 3094), fax (+39 02 5412 4344) or email (galli.mi@iplawgalli.it). The IP Law Galli website can be accessed at www.iplawgalli.it.

Endnotes

(1) See the ECJ decisions in Koninklijke KPN Nederland (C-363/99) and Campina Melkunie (C-265/00).

(2) See V Di Cataldo, “I segni distintivi“, Milan, 1993, page 69. In Merz & Krell (C-517/99) the ECJ broadened this definition, stating that signs which, although not descriptive, have come to be used customarily in the specific sector for which protection is sought cannot be monopolised.

(3) See C Galli, “Il marchio come segno e la capacità distintiva nella prospettiva del diritto comunitario“, ne Il Dir ind, 2008, 425 ff and Galli, “Marchio” in “Il Diritto – Enciclopedia Giuridica“, Vol IX, Milano, 2007-2008.

(4) See OHIM v Erpo Möbelwerk (C-64/02 P) and Nestlé (C-353/03).

(5) See C Galli, “Il marchio come segno e la capacità distintiva nella prospettiva del diritto comunitario“, supra note 3.